THE ASIAN CANADIAN INHERITANCE

As the Artistic Director of the Toronto Reel Asian International Film Festival (RA) from 2006-2013, I had inherited a heavy responsibility to further a discussion about Asian Canadian identity. The organization was created in 1997 during a peak in the Canadian multiculturalism movement, and was a response to the lack of representation of Asian voices on screen and behind the camera in Canada. The goal was to foster an appreciation and understanding of the diverse film and video work that was emerging from artists from Asia and the Asian diaspora. As the Artistic Director, I believed it was integral to maintain an inclusive and transparent selection process that considers the artistic merit of the work and its contribution to the form, its greater socio-political relevance, and its relationship to the local community. RA would of course need public and private funding, but more importantly it would need ongoing participation from local audiences and artistic communities. With this support came many ambitious expectations and measures of success that continue to influence the direction of the organization. The following highlights how a festival like RA responded to many issues brought up in 1990s, the core activities and creative solutions that have taken place, and some of the current challenges RA faces.

In Yellow Peril Reconsidered (1990), writer Monika Kin Gagnon highlighted key time periods in Canadian History that specifically targeted Asian Canadians such as the Chinese Head tax (1885-1923) and Japanese internment (1941- 1949).[move to endnote à Monika Kin Gagnon, “Belonging in Exclusion,” Yellow Peril Reconsidered (1990): 13.] However, even though Asian Canadian communities had actively advocated for recognition and redress for decades, few artists made work that represented a distinctly Asian Canadian perspective until many years later. In 1988, the National Association of Japanese Canadians succeeded in negotiating a redress settlement with the federal government and in the same year the Canadian government initiated the Multiculturalism Act. The 1990s spawned films, organizations, and heated debates devoted to a discussion around diversity and identity politics.In 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper made an official apology for the Chinese head-tax and the Canadian government established a fund for community projects aimed at acknowledging the impact of past wartime measures and immigration restrictions on ethno-cultural communities. Debate across Chinese Canadian communities escalated and filmmakers who took on publically funded projects dealing with the issue faced accusations of propaganda. By 2006, when RA celebrated its 10th anniversary (and I started my eight-year career as the programmer), there was already so much scrutiny around the multiculturalism agenda and backlash/resistance from the creative community and the community at large. These tensions pointed out the problems of multiculturalism initiatives, questioning how film and media perpetuated the victimization, appropriation, tokenism, or worse—superficial celebration of race. There was clearly a resentful sentiment from generations of artists who were exhausted by the burden of representation and the complex sensitivity around identity politics.

Founded in 1997, RA started as a small grassroots screening series and has since grown to be Canada’s largest pan-Asian film festival. Toronto’s Asian community alone makes up over 30% of the city’s population. RA has expanded its reach beyond downtown to the Toronto suburbs. RA is attended by more than 12,000 people over 10 days and offers a combination of Canadian and international films; however, it is not sufficient to simply present a diverse slate of work. It is essential to actively approach activities in diverse and accessible ways; to maintain a flexibility that is fresh, engaging, and exciting; and all the while to be professionally organized and respectful to RA’s founding core values and the values of its funders. RA has taken on year-round education programs in public schools, outreach to new communities, professional development (panels, workshops, and networking), and the support of the creation of new work through commissions and awards.

The predicament of the organization is to serve all of its constituents. While trying to cover a range of issues affecting the Asian region and people of Asian heritage around the world with the programming, the art work must also be representative of a Canadian perspective. The annual Asian Canadian Spotlight is a core program at the festival, featuring both emerging and established filmmakers and artists including: Wayne Yung, Ann Marie Flemming, Midi Onodera, Mary Stephen, Simon Chung, Ho Tam, Lesley Chan, Paul Wong, Desiree Lim, Lily Eng, Michael Fukushima, and Richard Fung. To consider some examples, Richard Fung, Paul Wong, and Lily Eng each have a distinct body of work; however, I would like to describe some similar sensibilities that have helped forward the discussion around Asian Canadian identity. These films tend to unravel master narratives through challenging conventions of form while exploring perspectives by turning toward the body to expose uncomfortable realities. They unpack problematic notions of national identity, while avoiding the trap of perpetuating simplified power dynamics and singular timelines that keep Western theory at the centre. They break open stereotypes that imply that visible minorities have another place of origin, another place to which they belong. They make room for ongoing conversations and challenge viewers as active participants in the discourse.

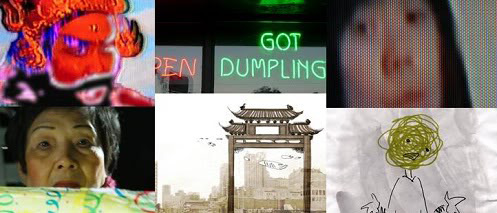

In Rex vs. Singh (2008), Richard Fung and his collaborators Ali Kazimi and John Greyson deconstruct a court transcript from 1915 trial that took place during a 20-year period when an inordinate number of men tried for sodomy in Vancouver were Sikhs. Staging scenes from a trial in four different ways—first as a period drama, second as a documentary investigation of the case, third as a musical, and fourth as a deconstruction of text—the video reveals not only a history of systemic homophobia and racism in Canada, but also how one moment in time can be explored and interpreted from a wide range of angles. The importance of experimenting outside of conventions in order to establish space for new discourse has never been more evident. Intentionally questioning mainstream cinematic tropes is an act in defiance in itself and perhaps provides a more accurate reflection of society today. Spotlight on Paul Wong in 2008 celebrated Wong’s uninhibited appreciation for the abundance, accessibility, and limitlessness of the medium, and included a vast range of presentation components including a bus tour with video and performance, public library and gallery installations, and several screenings. Spotlight on performance artist Lily Eng, looked at the Asian Canadian identity from the female perspective and highlighted a traveling exhibit that she spearheaded titled “But Women Did Come: 150 Years of Chinese Women in North America.” Her body of work was an intense hybrid form that was influenced by her formal training as a ballet dancer and kung-fu martial artist. This combination of East and West ,a fusion of Asian Canadian identity, was quite taboo at the time—now such an approach to art practice is embraced for uniqueness and innovation.

Sprung, 2013, Toronto Reel Asian International Film Festival. Sprung Commission 2013: Waack Revolt — A Dance Film by Sonia Hong, Emily Law, Diana Reyes, Between Us by Randall Okita and Andrea Nann, Paruparo by Sasha Nakhai and Catherine Hernandez, Friend Dance by Tad Hozumi and Mark Cabuena, and Restorative Structure by Dean Vargas and Lauren Cook

Since 2007, I have been successful in launching a number of community collaboration projects with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts as part of RA. The projects include: Sprung (2013), Suite Suite Chinatown (2010), and Empty Orchestra (2008). Each rendition had a live component and brought filmmakers together with unique performing artists representing a range of hybrid forms. Collaboration was a central component as the purpose was to build stronger ties across artistic disciplines. The experience gave participants a rare opportunity to work together outside of their usual roles, in order to learn about each other’s processes and art forms. These relationships developed into an expanded dialogue about how both media and performing art forms represent cultures, histories, and identities. The projects were seen as refreshing and original while they also touched on so many themes including,gender/sexuality, youth subculture, hip hop, migrant workers, mental illness, family, nostalgia, transformation, individual expression, collective identity, commodification of culture, and resistance.

Suite Suite Chinatown, 2010, Toronto Reel Asian International Film Festival.

Aram Siu Wai Collier, Lesley Loksi Chan, Lillian Chan, Heather Keung, Serena Lee, Howie Shia, and Joyce Wong

To understand the Asian Canadian context, it was essential to take on a more transnational perspective. The impact of forced migration, systematic racism and oppression is definitely not exclusive to a Canadian history. The work presented at the festival covered a huge range of issues and histories—even in one festival the conversation could span from Asian American activism, North Korean defectors, industrialization in China, race riots in Malaysia, sex workers in Japan, illegal migrant workers from Burma, and so on. There has recently been more internationally successful Asian Canadian filmmakers who have made documentaries about socio-political issues in Asia, such as Up the Yangtze by Yung Chang, Last Train Home by Li Xin, Tiger Spirit by Min Sook Lee, and The Defector by Ann Shin. While there has been a decline in interest in work that focuses specifically on the Asian Canadian perspective, it is positive to see that Asian Canadians have the freedom to make and distribute films about political issues abroad, and to further the focus on international human rights issues. However, there is definitely a reason to be wary about the impact of these works have on the understanding of Asian Canadian identity. There is a danger that these films reiterate images of countries in Asia as impoverished, abusive to human rights, corrupt and/or under political turmoil. Through an international perspective, the investigation into how the Asian identity is created and understood through film is even more complex. There is a global need to revisit discourse around the creation of identity and racism in media, even as artists aim to define ourselves as distinct from our colonial past and oppressive histories.

As the injustices of the Canadian past are ameliorated through apologies and forgotten by new generations, and as model “visible minorities” have become more recognized and reputable in the mainstream, public support for the multiculturalism agenda in the arts fades; there is increased pressure for arts organizations to secure more support outside of public Canadian funding. Therefore organizations must prove their significance not only by increasing profile media coverage, educational activities, and industry professionalization of the artists represented, but also by the reporting of large and diverse demographic numbers. All of this is somehow diffusing our distinctly Asian Canadian identity and resulting in one of the festival’s biggest challenges: what is the organization’s identity and how does its identity influence its supporters and potential supporters? Contrary to the independent work of artists like Richard Fung, Paul Wong and Lily Eng, who broke apart restrictive ties to countries of origin, RA has become increasingly focused on presenting an international identity, one that appeals to larger audiences and international funders. They have become key stakeholders, and therefore a part of the “community” in which the organization is responsible to respond. A few big apolitical films, with well-known names, are sure to bring in bigger audiences, more media coverage and increased financial support. This solution may seem manageable, but has the potential to threaten the Artistic integrity of the entire organization.

As curators, we aim to provide a platform for insightful and unique works, but also we are in the position of needing to be deliberately mindful of the agendas of our supporters, sponsors and funders, and how their response to work presented may impact future support. As the festival begins to present more mainstream audience-friendly films, we must simultaneously make significant efforts to continue to support the growth of a local Canadian creative community through curated commissions such as Sprung, Suite Suite Chinatown, and Empty Orchestra. Due to the fun, youthful and collaborative nature of these projects, the experience was not necessarily political, and instead allowed for all audiences to engage at a wide range of different levels. While I am concerned by a shift away from the more direct and independent socio-political nature that was apparent in the work of many of the Asian Canadian Spotlights, these recent commissions prove to be promising in today’s context, as they are artistically focused, innovative and engaging new communities.

NOTES

1. Monika Kin Gagnon, “Belonging in Exclusion,” Yellow Peril Reconsidered, (On Edge, Vancouver: 1990), 13.

Images courtesy the author