RETURNING TO THE ARCHIVE: THE AFTERIMAGE AND MEMORY WORK

Over the years my body of work has looked into the family archive as a departure point for various artistic projects that have explored the intersections of memory and history. When one arrives at the edge of the archive, one is often confronted with images from the past that are difficult to capture, grasp, or even re-imagine. As an artist working through the material of memory, I often feel the burden of history and the ethical responsibility to care for these images and stories. The challenge is to consider new existences for them alongside the mainstream cultural production of “commemoration” that limits how history and memory are understood. In three of my most current works, Panorama Series I (2011), Yokai & Other Spirits (2012) and Mörkö (2012), there lies an engagement with the familial archive and its objects, images, ephemera and stories. Each project bears a different commitment to the ways in which we remember and forget.

Panorama Series I

The year 2012 marked the 70th anniversary of the Japanese Canadian internment — the Nikkei National Museum in Burnaby, British Columbia invited me to create a new installation to be included in a group exhibition called Yo-In Reverberation.1 Panorama Series I is a work utilizing video projection and a series of three small museum plinths displaying small, intimate personal photographs taken during the internment. These photos belonged to my father’s family and had been kept hidden away in an album. The photographs in this album contain no written details and it was the first time I had seen these images of their experiences in the camps.

Cindy Mochizuki, Panorama Series I, 2012, installation view from exhibition at Nikkei National Museum and Culture Centre, Burnaby, BC.

In 1942, under the Canadian government of Mackenize King, all people of Japanese ancestry living along the West Coast of Canada were to be uprooted from their homes. The BC Security Commission carried out the incarceration of nearly 23,000 men, women and children who were categorized as “enemy aliens” of which 75 percent of these people were either Canadian-born or naturalized citizens.2 At the end of World War II, Japanese Canadians were given the so-called choice to go “east of the Rockies” or to “repatriate” to Japan. Approximately 4000 of these Japanese Canadians, or kika-nisei (returned second generation), were dispatched to Japan on “repatriation ships.”3 My family chose to repatriate to Japan experiencing another level of racism and discrimination, this time as “Canadian foreigners”4 in Shizuoka and Fukuoka prefectures under conditions of extreme poverty and economic upheaval in postwar Japan.

In the installation, a video projection of a topographical view of the internment camp site is projected onto a 3’x 3′ wedge that is placed onto the ground to confront the viewer in the space. RCMP officer John W. Duggan took the source photograph presenting the view from above. The camera glides across this black and white photograph from right to left in a slow pan as if to trace the viewpoint of the RCMP officer surveying the area. These photographs, much like postcards from the past, present an austere and distanced perspective, a melancholic representation of Canada’s dark past. The photograph depicts orderly rows and rows of wooden houses buried deep within the landscape of the interior of BC.

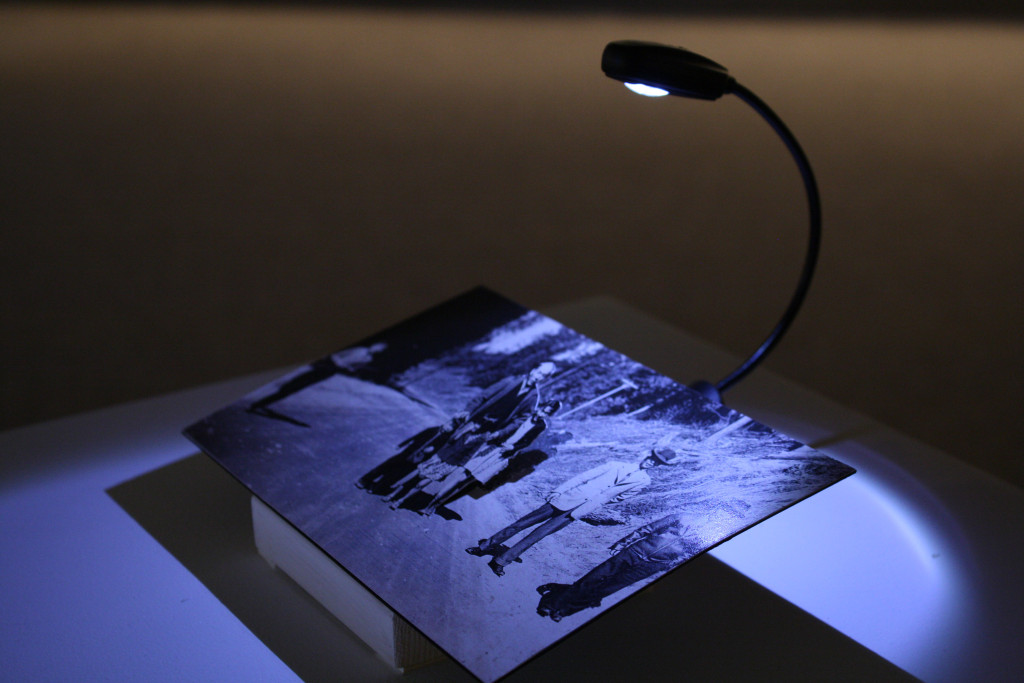

These snapshots of the camps were juxtaposed next to four small displays of photographs that were taken with a more intimate gaze and proximity. Gathered from my family’s private collection of images, we see an image of my father and my uncle, the Walnut Grove berry farm that was confiscated, and a snapshot of camp life with my grandfather and his children out for a walk in Slocan Valley. These images are placed alongside ephemera including a small digital projection of a video I made in 2004 of the river in Slocan. All of the still images are lit by a small LED light that casts shadows in and around the figures in the photographs — all the figures in each photograph are slightly raised using a paper-cut technique. Some of the photographs of the camp experiences were taken by an unnamed photographer using a pinhole camera. Other images were taken by what I would assume were smuggled cameras — all cameras and recording devices were confiscated from families5 during the internment.

In making this work, I am presented once again with the difficulty of making sense of these images and the events that were told to me through the voices of now-aging relatives. To return to the family archive is to be asked once again to re-enter the narrative of trauma and to re-imagine these sites of memory. At the same time I am concerned with a very complex understanding of the commodification of memory through commemoration and remembrance. How do I fill the space of absence without monumentalizing history? When there are several forms of cultural productions and public artworks that are created for the purpose of monumentalization, one needs to consider the ways in which remembrance is performed. Does the artwork perform the memory work for you or is the audience able to actively engage in the acts of remembrance?

Cindy Mochizuki, Panorama Series I, 2012, installation view from exhibition at Nikkei National Museum and Culture Centre, Burnaby, BC.

I position my practice within the context of a generation that speaks after the fact. Marianne Hirsch describes this process as postmemory, a term used to describe the generation that has no direct experience to the historical event/trauma itself. Postmemory describes the relationship that the “generation after” bears to the personal, collective and cultural trauma of those who came before. They “remember” only by means of the stories, images, behaviors and silences among which they grew up. These relational experiences were transmitted to them so deeply that they seem to constitute memories in their own right. The form of remembrance makes the connection to its source — it is mediated not through recollection but by imaginative investment and creation.6

Yokai & Other Spirits

Another of my multi-media installations that explores a movement through archives is the installation, Yokai & Other Spirits (2011).7 The commissioned project offered another methodology of working in the archive that provided me with another form for dealing with the historical material. Rather than the direct witnessing of historical images, this process allowed me to move into the archive by way of the hand-drawn line. In this example, the artist, rather than circling the parameter of the archive in search of meaning, passes through the material by direct tracing.

Cindy Mochizuki, Yokai & Other Spirits, 2012. Blackwood Gallery, the e|gallery, Mississauga, Ontario.

Photo by Robin Li

Yokai & Other Spirits was originally commissioned by Reel Asian and LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) as part of The Lost Secrets of the Royal project. Four Asian Canadian artists were asked to respond to Colin Geddes’ donation of an archive of incomplete and decaying 35 mm films from Hong Kong that were salvaged from the basement of what is now Toronto’s Royal Cinema. The only stipulation was that the items within this collection were to be used and transformed into new works.

In this installation, I decided to work with analog methods of film production and experimented with the form of rotoscoping. Rotoscoping is the animation technique of tracing original frames (24 frames a second) from the 35 mm film using the Oxberry stand. Through this method of re-documenting, I would draw each frame by hand, leading to thousands of traced images from the film. The cut of the film was determined by where the archival material would get jammed or break apart, in effect stopping the linear path of tracing each scene. The hand-drawn frames are then individually scanned and digitally output as animation or moving images. Yokai & Other Spirits is a reworking of a pivotal moment in the movie Happy Ghost 3 (by Johnnie To) where the young pop star, a ghost played by Maggie Cheung, calls “home” through various phone booths in the city. The installation, which no longer bears much surface resemblance to the source film, echoes my artistic interests in trying to create the immersiveness of the key moment in the film and also speaks to the impossibility of re-creating the linearity of this disintegrating form.

These kinds of spaces of cultural production and opportunity gave me new ways to enter this discourse of history and to remain open to its capacity to transform through the imagination. The installation offered a shift in the way I now navigate through the flows of memory work and the way we perform acts of remembrance. The archive is a process rather than a repository and it is a place that I will return to from time to time, but always with the intention to turn the archive from its inside out. Rather than standing back to observe the archival items, as an artist I will materially move through and work with the objects and images, giving them a sense of life and recovery.

Mörkö

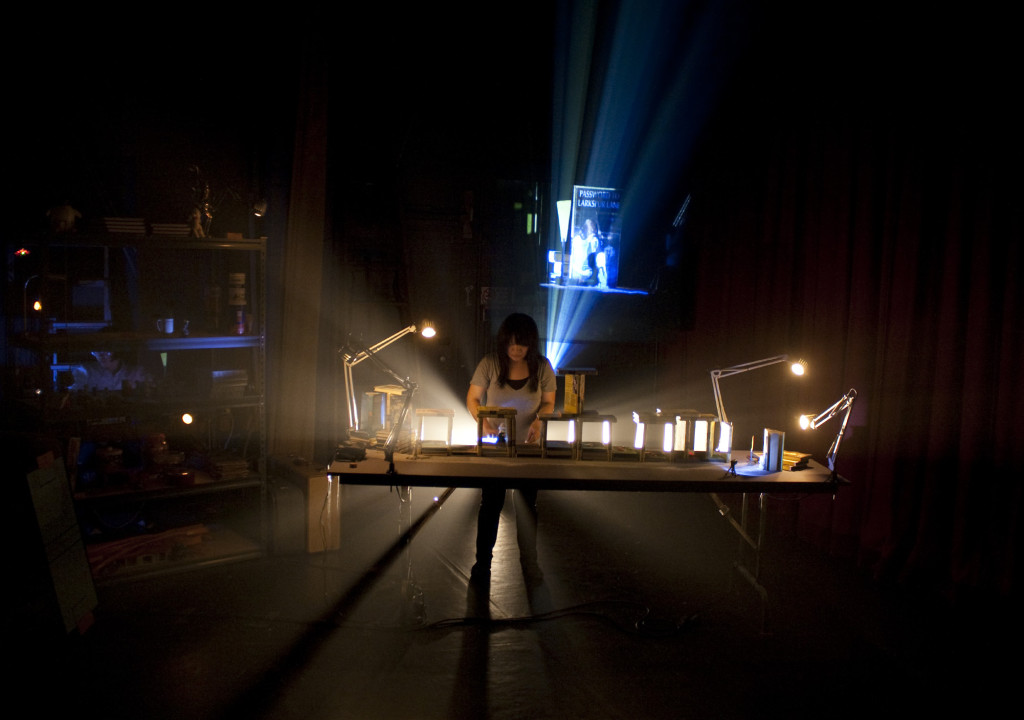

Based on a collection of interviews from a wide range of 30 Vancouver residents about “monsters”, I worked with an artistic team to create Mörkö (2012),8 a 40-minute performance that shapes a portrait of a city through the “monstrous”— a space, creature or thing of fear that we often conjure in our everyday lives when faced with the unknown. Through combining audio, animation and performance, I looked at a collective response to contemporary forms and notions of fear. I am the sole performer, building a landscape using only the audio recordings from the interviews and objects found in a basement closet of my childhood home. The room was once the family photographic dark room. Later it became a storage space filled with knick-knacks and other long forgotten cast-offs. The performance invited an intimate audience of 30 to engage in a space of listening and watching. At the heart of the soundtrack is a recorded conversation between my mother and I about what objects to keep and what to let go. The work reveals the complex realities of familial dislocation; my mother, as a first generation immigrant, has tirelessly collected everything from our childhood — a collection that reveals plenty about class, race, language and the complex reality of dislocation through immigration. These objects include a collection of old Nancy Drew murder mystery books, plastic Slurpee and rare Dixie cups, a Mattel toy car set and miniature tea sets.

Cindy Mochizuki, Mörkö, 2012. Russian Hall, Vancouver,BC.

Photo by Tim Matheson

Annette Kuhn refers to the practice of memory work as “the active practice of remembrance which takes an inquiring attitude towards the past and the activity of its reconstruction as memory.”9 Images of the past and of “history” have always haunted me, causing a certain paralysis when it came to considering possibilities for ethical ways to bring these images and stories forward into the contemporary present with a sense of care. Both Yokai & Other Spirits and Mörkö released me from that impasse by giving me the agency to move through subsequent archival work with a sense of ease.

My current work in production is a multimedia installation called dawn to dust, a fictional memoir based on the lives of family members who chose repatriation to Japan. In this return to the narrative of the Japanese Canadian internment, I use animation as a form to open up a space for imagining another place and time and to create another lens to re-witness history. As part of my process, I work with testimonies of family members who were exiled from Canada as children to postwar Japan. I combine hand-made creatures, puppets, sets, rotoscoped animations and video, using magical realism to tell stories of survival that challenge narrative notions of “truth.” The ability to transform mundane reality into something strange-but believable is possible through the medium of animation. Animation offers the potential to bring elements of beauty, hope and change into what is perceived at the same time as a heightened space of racism.

The conventional methodologies of commemoration often perpetuate an act of forgetting, instead of considering the ways in which the viewer can continue to remember. Often times a monument or a plaque can present a monumentalized form of history that already provides the audience with cues as to how to “commemorate.” In contrast to these ways of remembrance, my practice attempts to challenge convention and bring ways of witnessing that actively engage memory work and provide other ways of facing historical trauma.

The archive is an ongoing site for critical investigation where one can reconstruct one’s identity and connect with a sense of shared origin and place. When factors such as home and identity are affected by traumatic events and shaped by racism, the ability to connect becomes burdened by the weight of history. A family album has the capacity to “gather us together to enact communal ties” and to “shape our collective identities, symbolize the values and goals we share, and form the basis for imagining and planning a future together.”10 Here, the ghost within the archive then becomes the spirit to move us forward, to imagine new possibilities of remembrance and memory work, and to move towards the possibility of transformation and change.

NOTES

1. Yo In Reverberation, group exhibition, Nikkei National Museum, Burnaby, BC. May – August 2012.

2. Roy Miki, Redress Inside the Japanese Call for Justice, (Vancouver: Raincoast books, 2004), 2.

3. Tatsuo Kage, Uprooted Again Japanese Canadians Move to Japan After World War II, Translated by Kathleen Chisato Merken, (Toronto: Ti Jean Press, 2013), 18.

4. Ibid., 102.

5. Roy Miki and Cassandra Kobayashi, Justice in Our Time, (Talon Books: Vancouver, 1991), 24.

6. Marianne Hirsch, “Mourning and Postmemory” and “Past Lives” in Family Frames: Photography Narrative and Postmemory, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 22, 49.

7. Lost Secrets of the Royal, four-person exhibition, Blackwood Gallery, Mississauga, ON. November – December 2011. Commissioned by LIFT and Toronto International Reel Asian Film Festival.

8. Mörkö is an interdisciplinary performance integrating sound by Emma Hendrix and live video and animations by Cindy Mochizuki with direction by James Long.

9. Annette Kuhn, “A Journey Through Memory,” Memory and Methodology, Edited by Susannah Radstone, (New York: Berg, 2000), 186.

10. Kirsten McAllister, Terrain of Memory A Japanese Canadian Memorial Project, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010), 12.

All images courtesy the author