Paul Wong

Heather Keung is an independent artist and curator, former programmer with Reel Asians. I have programmed both of these works before and I saw a lot of new stuff today seeing them side-by-side on the big screen. I’ve seen Karin Lee’s work as an installation and I’ve seen Ali Kazimi’s work at festivals. I have also programmed both of these works at the Chinese Classical Gardens in Vancouver. They are astonishing when viewed side by side and amazing in this context. You both work with historical archival materials, how did you arrive at this material and how did you decide to reenact and present it in this way?

Karin Lee

With Shattered I wanted to commemorate the 1907 riots and looked at five different versions of the same story. In the Chinese version you see a lot of buildings with glass and, of course, in Chinatown all the buildings were shattered. Now Concord Pacific owns much of that property, which is China and Hong Kong interest. I utilize some of those images and reenacted the riots based on historical materials that we had translated from Chinese records of the riot and also materials from the Japanese consulate.

I was interested in giving a voice, during my youth I was angry at my grandparents and my parents for being so complacent. I did not understand why they wouldn’t fight against racism. I did not understand that it was from the generations of racism they had experienced. There was no education about any of this, there was no information passed down to me, I found this confounding. I was inspired to hear the voices of those who wanted to fight back against the rioters during the riots.

Ali Kazimi

I love the dialogue of Karin Lee’s work, because when I look at the images of the riots I can hear the sound, it’s about the shattered glass. I’ve seen the original photographs that Mackenzie King commissioned of the riots when to convey the investigation, those cyanotypes are beautiful. The glass really jumps out, the violence inherent in those broken panes of glass is absolutely visceral.

Paul Wong

In each of your works, you are playing with someone’s concept of truth, you are making your own version of the truth and you are spinning together different versions of truth, so what is the truth?

Ali Kazimi

As an artist working with archives you are trying to make meaning from scraps. You are essentially trying to piece together a puzzle with huge chunks of information missing. In some circles, this is part of the objective process. I do not think it is objective at all. I think as artists what we are trying to do is to show the subjectivity of that process and certainly in Rex vs. Singh (2008), I was invited by John Greyson because of the work that I have done earlier on the Komagata Maru and Richard Fung was asked because of his work on early Chinese migration. When we first sat down we thought we would play the transcript first as a classical courtroom drama. We used Witness for the Prosecution (1957) as a touchstone; this was a classical courtroom drama from the 50s. We used that as a way of setting what this notion of truth was. All the information we had was based on the transcript, and this was supposed to be the ultimate truth. This was the written document that has it all but then we realized, “does it have it all?” What gets literally lost in translation? What does the transcriber write? What are the errors made by the transcriber? As we were reenacting it we discovered that the actors themselves were making errors, which we deliberately left in. If you notice the transcript in Richard’s version, it doesn’t quite match what the actors have said. We are playing with this varying idea of “what is truth?” I wanted to contextualize in a way that deconstructed truth and give it a historical framework in which the other three versions could emerge.

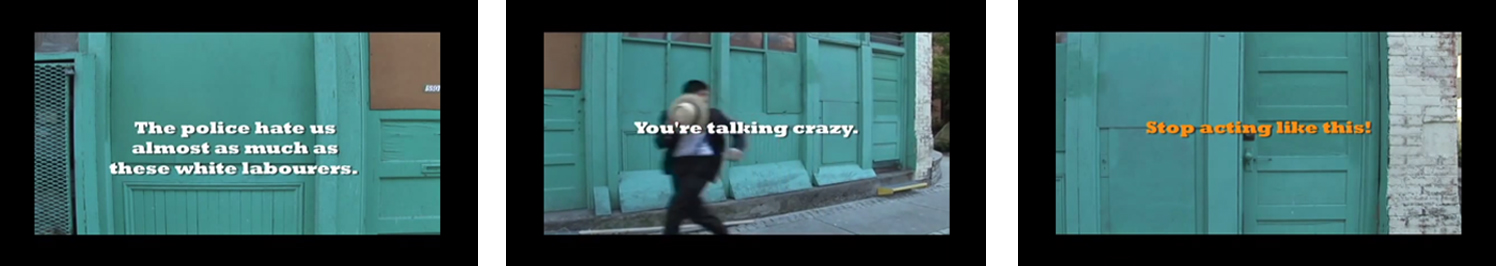

Images: Karin Lee, SHATTERED: The anti-Asian riots of 1907, 2007. Images courtesy the artist

Karin Lee

I love the three versions. So playful.

I think for Shattered the diversity of voices is truth for me. I wasn’t just focusing on the Chinese or Japanese version, but to also look at what the labourers were going through at the time. As Ali said when you are looking at archival materials you are trying to take as much as possible to be able to give it meaning. From Canadian sources it was a very limited. It was Mackenzie King’s report, and in newspaper articles that were specific about what the riot meant. When we went to look at Chinese language reports and what they reported in Japan and in Singapore, we were given different accounts of what had happened. It became a fuller truth for what happened at that time.

Based on some of the Chinese articles, there was a lot of divisive opinions in the community as whether to fight back or not. I also spoke to elders and asked, “were the Chinese cowards?” “Why didn’t they fight back?”

They said, “no, they didn’t want to insight more violence, you should not fight violence with violence.”

Heather Keung

So the lynching of the individual or, I guess, the suicide, has that ever been reopened? We recently had Christine Choy in Toronto. She revisited Who Killed Vincent Chin, it is a very important, layered retelling of the same narrative over and over until it unravels in a different way. I was wondering if that was influential?

Karin Lee

No. It remains an unsolved case that I haven’t revisited, maybe in the future.

Ali Kazimi

One of the interesting things about the 1907 riots in the current context of Komagata Maru is that the riot was sparked by hysteria that was building up about another ship, the Montiko that was rumored to be carrying 2000 Asiatics that was landing imminently. The Montiko was on its way, it was carrying 1100 people, 900 South Asians, the rest were Chinese and Japanese migrants. The ship was not allowed to land, they were held in detention while the riot was going on, they were finally allowed to land when things had quieted down. So this idea of the dreaded ship carrying holds of people is something that continued to manifest itself. For the Komagata Maru, one of the initial strategies by immigration authorities was to say that there would be another riot if they let these people on shore. In many ways the 1907 riots haunted the arrival of the Komagata Maru.

Karin Lee

In the Japanese version, there is a marked difference between the way that the Japanese Canadian community dealt with the rioters. The Chinese didn’t use guns and they didn’t fight back, they boarded their shops from the inside. But by the time the rioters went to Japan town, barricades had already been built up and the community was ready to fight back. They had their Kendo swords and they had their guns and they had everything to keep the rioter’s out with the assistance of some of the police. It was a difference between what each community’s philosophy was. Also I think for me, it was a reflection of the strength of the government because at that time the Chinese government was very weak and the Japanese government was much stronger.

Ali Kazimi

Yes, I was going to add the way that Mackenzie King dealt with the two different communities was quite different. In the Japanese instance, every shop and every business was photographed and these are actually amazing portraits of people at the time. You can see the trauma on their faces as they stood in front of their business that had been absolutely destroyed and I found these amazing little notations about people actually refusing compensation. There would be just a small line saying, “refused to accept compensation”, and you wonder what is going on there. The geopolitics of the time is very important because Japan was an ally; there was an Anglo-Japanese defense and economic treaty that protected the west coast of Canada. Japanese cruisers regularly came to Vancouver and their arrival was celebrated because they offered protection for the west coast. There was a great geopolitical play also going on, Mackenzie King would not quibble with any of the claims on the Japanese side but on the Chinese side there were all these negotiations going on for the longest time. You can see in his record that he didn’t entirely believe in all the claims, as Karin said, it had to do with the power of the state at the time and their relationships with the British Empire.

Heather Keung

What I thought was amazing in Continuous Journey (2004) is what you (Ali Kazimi) brought up about the history of the South Asian communities here in Vancouver, which was very active and involved. You were talking about the Chinese community, how they were feeling silenced, but right away the South Asian community in Vancouver was kind of a front line advocating. It is a very interesting part of the narrative can you elaborate on that?

Ali Kazimi

A friend of mine, Johanna Ogden has done some amazing work in terms of the relationships between the various communities. She is from Astoria, just south of the boarder where the South Asian revolutionary Ghadar Party emerged. Johanna wonderfully shows the way they were inspired by the organizers within the community of the Chinese Nationalists with their fundraising and political organizing that they were doing for Sun Yat-sen who visited the west coast and Vancouver several times. They were also inspired by the Finnish Socialists who were doing amazing work in terms of labour relations, but also engaged in deep conversation about the state of the world. I think one of the things that was happening was this great cross-pollination of political ideas between the communities and there is a lot of work being done now uncovering those histories which for me is the next exciting step.

Image: Ali Kazimi, John Greyson, Richard Fung, Rex vs Sing, 2008. Image courtesy the artists

Heather Keung

I am interested to see those various communities’ plans moving forward. Do you know about that?

Ali Kazimi

Yes, the Ghadar Party, was calling for an armed revolt in India after the Komogata Maru was forced to turn back. That moment became a great catalyst for the Ghadar Party to go back and start a revolt in India. Thousands of people left and the community in Vancouver was pretty much decimated because they either, thousand left for India and the rest went south to the US. Those who went to India were betrayed and the revolution itself was betrayed. The British Intelligence was on to them and most of those people were arrested on arrival. At least two activists in Vancouver are hung for their so-called seditious speeches.

Paul Wong

Let’s invite questions from the audience.

Audience 1

Karin I want to go back to the silencing that you talked about, there was such a silencing in the community for a long time. We are now starting to unearth the silence because people had suppressed the truth. I produced a documentary on Japanese internment, we talked to the community, and they didn’t want to talk because they were ashamed of their own history. Can you elaborate on the challenges to get people to speak and how we can honour their truth?

Karin Lee

I talked with people at the Chinese Benevolent Association, because they are the oldest organization in Vancouver’s Chinese community. They said most of their records had been burned but there were a only few elders who were young in 1907 willing to talk to us. Why did they not want to talk to us? Because it was shameful to be Chinese because they felt that they have been targeted for decades, there was no reason to voice, there was no reason to fight for your rights which was difficult for them. The War Vets are a completely different generation; they wanted to move forward, to get recognition and to get political franchise. It is always difficult to get older people to tell you their stories and if they do, they don’t want to go public.

This was originally an installation that we mounted in Chinatown in Shanghai Alley and in Japantown at Oppenheimer Park. What I wanted to do was engage with the community so the dialect of the Chinese that you hear is the dialect that would have been spoken. It is not Mandarin or Cantonese but the village dialects of the people living in the area at that time, we did the same with the Japanese version. I wanted to use voices in a way that would confront viewers in the community by hearing the voices of the people being threatened by the riots at that time.

Audience 2

Ali, could elaborate on the pocket music montage? How did that idea come about? I loved it but I also want to know more because I feel like I am missing part of the joke.

Ali Kazimi

it’s no my version, it’s John’s version. It is difficult to speak for John so I will tell you what I know. John noticed in the transcript that there were a lot of references to change. The 75 cents and whose pocket it was in. So there were references to change and pockets, lots of pockets. He started looking at how he can draw from pockets and how he could put it in multiple ways. It confounds viewers so you need to see it multiple times to solve the puzzle. Also, he uses a lot of reference to popular music, John has had a long standing collaboration with composer David Wong who is amazing. He can sound like anybody, and he did all the voices. John rewrote all the lyrics, the lyrics were based on references to pockets and control; social and legal control under the context of Empire.

Paul Wong

John Greyson is the Canadian who just served 50 days in an Egyptian jail. He is a filmmaker and great friends of ours, he will be here for the Queer Art Festival in July and will be showing his video Prison Arabic in 50 Days (2013) that he made of his incarceration.

Paul Wong

All of your works have great creativity and ambiguity, which separates you from the so-called truth makers and conventional documentarians who always purport to be the telling the truth. I think great works of art have ambiguity which force us ask more questions. Both your works do that. They rip things open and offer more layers. Why do you think ambiguity is evident in your work?

Ali Kazimi

I think that the worst thing that history does is to make people passive recipients of facts, figures, dates you are not supposed to question the historical narrative that you force-fed. History becomes painful when it addresses a past that engages with the present and when it opens up spaces for audiences to ask question. Asking questions means engagement and hopefully that is what we are trying to do.

I love Shattered because it really gives a voice for archival history that goes beyond the traditional archive that we all know of that moment and really puts us on the other side. I found that remarkably perfect.

Karin Lee

Thanks.

Ali Kazimi

Before I forget, I want to acknowledge something that Paul said right in the beginning because really we couldn’t be having this conversation without the amazing hard work that you (Paul Wong) did. I really mean it because I know in the course of making works around race still continues to be a huge challenge, enormous challenge to get the program because there is a great discomfort around the issue of race. Mention race in a large mainstream audience and everyone start squirming at their seats but that squirming also reflects a kind of resistance. What you did 25 years ago was amazing and really opened up a whole set of possibility for people either from the Arts Council where those conversation becomes really important and feisty and led to people like myself being funded so thank you.

Paul Wong

Artists continue to blaze the trail. We do not need to get permission to speak our truths in provocative, new and different kinds of ways. I have seen what a little bit of permission that we have been given and what we have accomplished with very little. Artists are like not like everyone else, we can make great mistakes in trying to find the truth. We can go to places where other forms cannot or other industries will not. Artists can take us to other imagined places; you all have done a wonderful job in doing that with your works. Thank you for being here.